Whistleblowers Are the Conscience of Society, Yet Suffer Gravely for Trying to Hold the Rich and Powerful Accountable for Their Sins

Why Don’t More People Support Whistleblowers? Legislatures Should Provide the Protections Whistleblowers Deserve

Author: Ashley M. Gjovik

Originally published in CovertAction Magazine on April 25 2023.

[Author’s Note: I blew the whistle and was met with an experience so destructive that I did not have the words to describe what happened to me. I set out to learn if what happened to me is a known phenomenon and, if so, whether there are language and concepts to explain the experience. I found it is well studied. This article focuses on experiences like mine, where a still-employed whistleblower takes disclosures of systemic issues public due to inaction or cover-ups by the institution. This article does not intend to discount the other varieties of whistleblower experiences; instead, it seeks to explain, expose and validate the turmoil many whistleblowers in similar positions are often forced to endure alone. You are not alone.]

Introduction

The term whistleblower is thought to originate from Victorian England, where, when a crime was committed, the policemen would blow a whistle while chasing the criminals to alert the public of the crime. Today, much like those historic figures, modern whistleblowers who spot misconduct “blow the whistle” and alert the public of the threat. The whistleblower acts as an early warning signal and defense mechanism of the common good.[1]

The term “whistleblowing” can be used very broadly to refer to an act of dissent, or it can be defined in a precise way, such as defined by statute. Whistleblowing generally seeks to reveal abuse and malfeasance, and to promote accountability. Publicly known whistleblowing cases often concern issues of societal importance, like human rights violations, environmental damage, health and safety dangers, miscarriages of justice, and systemic corruption.[2]

Despite the importance of their actions, named whistleblowers are often subjected to oppressive and stigmatized labels—like “snitch” or “leaker.” Those discussing whistleblowers often treat them as some sort of sympathetic antagonist, the person is publicized instead of the disclosures, and coverage is constrained to interpreting actions only through formal laws and norms with a deference to industry.

Perhaps due to the potential disruption whistleblower disclosures can cause to established systems, there is a positivist urge to quantify and label whistleblowers. There have been extensive—and generally fruitless—studies searching for a special recipe of human characteristics that lead one to become a whistleblower. This is misguided and distracts from whistleblowing as a moral challenge anyone may have to face. Studies are predictably conflicted as to the whistleblower’s most common gender, nationality, race, ethics, or age.

There does seem to be positive association with education, honesty, strength of spiritual faith, and morality—only subjective characteristics. Studies have shown nearly half of all workers never raise any concerns at all. Other workers may raise concerns and the employer will actually quickly address the issue, or conversely the employee may give up after the first failed attempt. It’s clear the distinguishing factors that sets whistleblowers apart from other employees are the very acts of speaking out and escalating when the first attempt fails.[3]

The attempted classification of scientific categories to predict whistleblowing have been debunked and cautioned for decades—yet it persists. Ignoring the issues that cause the person to come forward in the first place, many studies still focus on an endless search for data points to classify whistleblowers based on immutable and subjective categories.

At best, this is perhaps researchers attempting to flag categories to screen potential risks to power structures but, at worst, this is a disturbing quest to declare formal biological and social determinants of moral behavior. In modern history, “scientific studies” attempting to formally determine if people with certain immutable characteristics are superior or deficient related to basic human behaviors and activities has often ended in tribunals.[4]

There is also a flawed tendency toward a Foucauldian view of whistleblowers, celebrating the idea of “fearless speech” and viewing the whistleblower as a political actor who performs an act of resistance by speaking truth to power. This view is nascent—and only relevant at the earliest stages of whistleblowing or for those who blow the whistle after they are well out of harm’s way—while ignoring the predictable and devastating aftermath for those who blow the whistle while still employed.[5]

Far from some sort of fearless rebel, whistleblowers are often professional idealists and loyal organization adherents who were not aware of the dangers and consequences of disclosure. Instead, whistleblowers often earnestly trust their organization and believe it will take actions to address the issues raised. Similarly, military and intelligence whistleblowers are often conservative and patriotic.

Many whistleblowers speak up because they believe in formal procedures and justice, never expecting an antagonistic response. Many whistleblowers also expect that taking the matter to a regulatory body will finally deliver law and order to the situation, but instead are often met with even more threats and retaliation, now by the government agencies supposedly chartered to protect them.[6]

Having a Reason to Blow a Whistle

Deconstructing the process of blowing the whistle, there are two significant moral queries. The first is: When is it justified to blow the whistle at all? The second is: When is it justifiable to not blow the whistle?

Justification for blowing the whistle requires: an organization, policy or product that poses a serious and considerable harm to the public; the employee reported the threat to their supervisor (if feasible); and, if not addressed, the employee escalated further to the extent they exhausted all possibilities for resolution internally. If these requirements are satisfied, it becomes morally permissible to blow the whistle, though the person is not morally required to blow the whistle.[7]

An employee becomes morally obligated to blow the whistle if the employee has accessible, documented evidence that would convince a reasonable and impartial observer that the whistleblower’s view of the situation is correct; and the employee has good reason to believe that, by going public, the necessary changes will be brought about and harm will be prevented.[8] Because managers are almost certain to deny wrong-doing, a whistleblower needs ironclad evidence in-hand, and a whistleblower who can obtain this is in a rare and impactful position. When all five conditions are met, whistleblowing is a form of “minimally decent Samaritanism.” Indeed, many whistleblowers have described themselves as involuntarily compelled to blow the whistle and “having no other choice.” This is often in direct contradiction to the way society wants to view whistleblowers.[9]

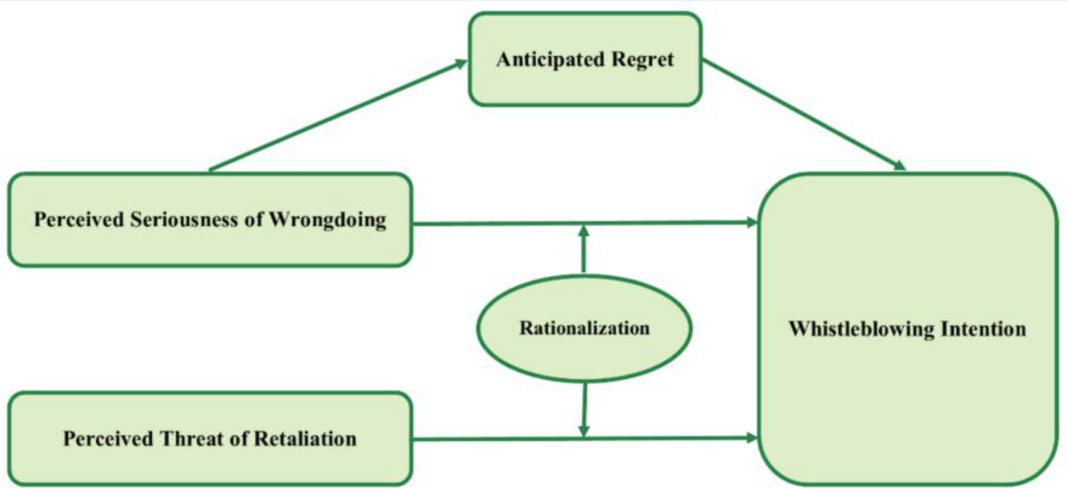

For those in situations where whistleblowing would be justified but not morally required, there is a moral and personal reckoning process. Functional considerations may be at play such as social policy, individual prudence, legal protections, socioeconomic status, expectation of loyalty to the organization, or organizational and professional norms. Regret functions to connect seriousness to intention, while fear of retaliation may trigger moral disengagement (i.e., dehumanizing victims) to reduce cognitive dissonance and throttle moral emotions.[10] In general, workers are most likely to blow the whistle on severe issues and intentional misconduct. In two-thirds of cases the whistleblower went to a regulator because their complaint was ignored by the company and, in ten percent of the cases, the whistleblower came forward because of a cover-up.

Whistleblowing is a dynamic process that takes time to unfold. Most people do nothing until they are convinced the wrongdoing is alarming: morally offensive and with considerable threat of harm. Most people have no idea what they are about to face, and may not have the information required to properly reckon with the decision to be made. Many disclosures are made in quiet good faith and the person would never think of themselves as a “whistleblower,” and thus also does not gather sufficient evidence that could withstand an imminent cover-up, nor would they have the perspective to actively identify, document, and navigate the reprisals about to unfold.[11]

Effective whistleblowing is “the extent to which the questionable or wrongful practice (or omission) is terminated at least partly because of whistleblowing and within a reasonable time frame.” This may be displayed in the organization launching an investigation into the whistleblower’s allegations (on their own initiative or required by a government agency), and/or if the organization takes steps to change policies, procedures, or eliminate wrongdoing. Few may be able to achieve these outcomes and those who do may still question if it was worth the sacrifice.[12]

Predictable Violence

Despite the appearance of whistleblower laws and protections in the United States, the inefficacy of these protections is demonstrated by the institutional violence used to silence, discredit and, ultimately forcibly remove the whistleblower from the workplace. Whistleblower retaliation is a severe form of violence and whistleblowers who disclose while still employed seldom anticipate the often-catastrophic consequences of their actions.[13]

On the other side, faced with a blown whistle, institutions instinctively react to minimize their culpability and damage. The standard management tactic is instigating mobbing by co-workers to then build a vague complaint against the whistleblower, which is then investigated and documented to impugn the whistleblower’s credibility and assassinate their character, and the whistleblower is then also formally isolated to “protect” the new farcical investigation.[14]

Ultimately, about 70% of whistleblowers will find themselves swiftly fired or forced to resign—usually the whistleblowers who took their concerns outside the company.[15]

Retaliation against whistleblowers is common and severe. Those who report externally and trigger adverse publicity can expect to meet “comprehensive forms of retaliation.” Those who blow the whistle on serious wrongdoing are expected to suffer “significant damage.” Whistleblowers often face retaliation to the extent it disrupts their core sense of self. The impact of whistleblower retaliation cannot be overstated.[16]

Disabling PTSD-like symptoms first start with self-doubt and then escalate in a spiral to a loss of sense of coherence, dignity and self-worth. This anxiety is felt for years. Compared to the general population, whistleblowers have much more severe depression, anxiety, distrust and sleeping problems. Some 88% of whistleblowers report intrusive thoughts and nightmares, 89% report feeling humiliated about the situation, and 87% report belief there was a hostile mob organized against them. The psychological impact has been compared to the grief associated with the death of a loved one, or a person’s mental state two to three weeks after experiencing a major natural disaster.[17]

In addition to counter-accusations and job loss, retaliation may include: demotion, harassment, decreased quality of working conditions, threats, reassignment to degrading work, character assassination, reprimands, denigration, punitive transfers, increase in workload, smear campaigns, surveillance, rumors, deny listing from their field of work, denial of promotions, overly critical performance reviews, double-binding, the “cold shoulder,” referral to psychiatrists, manufacturing personal and/or professional problems, exclusion from meetings, insults, retaliatory lawsuits, stalking, ostracism, petty harassment, abuse, bullying, doxing, vandalism and destruction of personal property, police reports and arrests, and even harm to the whistleblower’s own body through physical attacks and sexual assaults, to the extent of assassination.[18]

There are several known, confirmed whistleblower assassinations in just the last few years, including:

Eliud Montoya blew the whistle on a labor-trafficking scheme at his company, where undocumented workers were hired and their pay was skimmed—with the perpetrators stealing more than $3.5 million. In 2017, Montoya reported the scheme to his company management (a subsidiary of Davey Tree Expert Company), then four months later also reported the situation to the U.S. EEOC. Two days after Montoya took the complaint to federal regulators, three men at the company assassinated Montoya, shooting him to death.[19]

Another assassinated whistleblower was Babita Deokaran, the chief director of financial accounting at a Department of Health agency in South Africa. She blew the whistle on suspected corruption at Tembisa Hospital, flagging nearly £43m of possibly fraudulent transactions. The corruption is now suspected to also be connected to an organized crime ring. In 2021, Deokaran was shot dead outside of her home in a “hit-style” killing. Days before the murder she had warned her supervisors “our lives could be in danger.”[20]

In New York, Allyzibeth Lamont discovered her boss was paying employees under the table (not deducting payroll taxes). She reported the issue to the New York Department of Labor and planned to take the issue public. The employer testified he was nervous the labor complaint would now “get in the way” of his plans to open a new location, so he hired someone to assist him in assassinating Lamont. In 2019, Lamont was suffocated with a plastic bag over her head, then beaten to death with a baseball bat and sledgehammer, and her body dumped in a shallow grave next to a highway. The New York Labor Commissioner said Lamont’s killing was “the most heinous act of retaliation against a worker that the New York State Department of Labor has ever seen.”[21]

In addition to known murders, there are also several notoriously suspicious whistleblower deaths which are suspected to be retaliatory killings, including:

Frank Olson was an executive in the CIA’s Special Operations Division and MK-ULTRA program. Olson was involved in a number of ghastly secret chemical and biological warfare experiments and operations. Olson expressed shame about his involvement and compared some of the U.S.’s activities to “what had been done to people in concentration camps.” He told his wife he was deeply bothered about the germ warfare experiments in Korea, that he had “made a terrible mistake,” and contemplated quitting. There were also suspicions Olson planned to blow the whistle on the CIA’s connection to a mass poisoning event in Pont-Saint-Esprit in 1951. Shortly after failing a CIA interrogation in 1953, and a finding that he breached security protocols, Olson then “fell out of a window.” The witness, another CIA executive, could not provide a coherent explanation of events leading up to the fall yet, right after the “fall,” he made a phone call to an unidentified source saying “he’s gone,” to which the person replied “that’s too bad” and hung up. An autopsy found a blow to Olson’s head from the butt of a gun. The night before his death, Olson told his wife someone was trying to poison him and he feared for his safety.[22]

Karen Silkwood was a lab technician at a Kerr-McGee plutonium plant. In 1974, she reported to her labor union and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission that the plant had quality-control failures and lax safety procedures that put employees at risk of radioactive contamination. The union encouraged her to gather internal documents to corroborate her allegations. Less than two months later, she was contaminated with plutonium at work three days in a row, and then also found plutonium contamination in her home—all of which she alleged was intimidation by Kerr-McGee. Silkwood persisted, obtained corroborating evidence, including documents exposing that a significant amount of plutonium was missing from the factory, and got in her car to drive to meet with a New York Times reporter to share the documents. Silkwood was found dead in a car crash. The documents Silkwood obtained to expose Kerr-McGee went missing. It was later revealed Silkwood likely unwittingly collected documents that also exposed a nuclear smuggling ring.[23]

Cliff Baxter was a vice chairman at Enron and had raised a number of concerns internally about Enron’s dubious off-the-books transactions with private partnerships. Fellow Enron whistleblower Sherron Watkins noted Baxter’s dissent in her now famous memorandum to CEO Kenneth Lay. In 2002, two weeks after Baxter was first publicly named as an Enron whistleblower in Watkins’s memo, Baxter was found shot dead in his car with “rat-shot” (an unusual type of ammunition not easily traced back to the gun from which it was fired). Baxter had unexplained wounds on his hand and shards of glass on his shirt. A few days before his death, Baxter had commented about needing a bodyguard. At that time, Enron was engaged in the now notorious, extensive and obstructive shredding of incriminating documents and deletion of computer files.[24]

Based on the U.S.’s history of incredibly violent responses to labor organizing, it is probably safe to assume that, if large, powerful institutions could successfully murder their most threatening whistleblowers, they would not hesitate to do so.

The capacity for retaliatory physical violence may often be present (especially if the whistle is blown on an institution with a large private security force), and threats of violence can be exceptionally effective in silencing witnesses. However, threats of violence and attempts at assault are often not worth the risk to employers, as it may give the employee tangible proof of retaliation, an actionable complaint for law enforcement, and also lead to extensive publicity. Thus, employers seem most often to follow a playbook designed to initiate a self-destruction protocol through social and psychological violence, instead of direct physical assaults. [25]

Overall, 99% of whistleblowers report feeling harassed, 94% report bullying that left them fearful, and 89% reported confrontation and threats. About 14% of whistleblowers reported being physically and/or sexually assaulted. Retaliation is expected to be more severe when the person discloses information about systemic and deep-seated wrongdoing (as opposed to isolated incidents), or when whistleblowers go outside their organization to report to a regulator or journalist.[26]

Management will often continue to allow, if not actively enable or instigate, retaliation by co-workers. The corporation will pressure other employees to collude against and inform on the activities of the whistleblower. The whistleblower will concurrently be ostracized and shunned, with their disclosures scrutinized and minimized, in order to thwart their sense of purpose and community (factors often associated with depression and suicide). Some 50% of whistleblowers admit to thoughts of suicide.[27]

One of the most devastating forms of retaliation to a whistleblower is gaslighting. The corporation wants to deflect its wrongdoing, degrade its victims, and undermine the victim’s credibility as a witness. To achieve this, the institution enables reprisals and retaliation, then explains away those actions with excuses and misdirection, and then claims the whistleblower is overreacting irrationally, while also creating a mirage of concern and respect for the whistleblower. This psychological manipulation protocol intends to cause the whistleblower to question their own memory, perception, and sanity. To onlookers without context, the whistleblower appears inconsistent and unstable.[28]

Retaliation by official government channels is especially problematic because, while similar gaslighting is likely to occur, public opinion will generally view those processes as fair and independent while, in reality, those agencies were often created and captured by business interests.[29] Official channels also narrow the disclosures due to statutory terms and regulatory procedures, transforming the whistleblower’s experience of retaliation into an administrative and technical matter—which may be dragged out for years before commonly being dismissed without proper investigation. The institutional systems put in place to squash whistleblowers intend to leave the whistleblower, and anyone watching, to feel there was no point in ever coming forward.[30]

Similarly, the press has been known to publish adversarial coverage of credible whistleblowers, even on matters of great public importance. The press and pundits may participate in smears and discredit the whistleblower through racist and classist ideology, while concurrently parroting the institution’s unsubstantiated statements as conclusive fact. They may also frame the whistleblower and supporters as “conspiracy theorists” or otherwise untrustworthy, and push a hero-traitor paradigm. These tactics can be quite intentional, fueled by professional and partisan politics, and business interests. Institutions, especially the U.S. government, have even been known to reward journalists willing to push the institution’s biased views, and punish the reporters who tell the truth.[31]

Through the process of complex and holistic retaliation, a whistleblower’s identity will be disrupted. In order to counter the gaslighting, the whistleblower must accept a variety of institutional betrayals and tend to their resulting moral injuries. Like the prisoner freed from Plato’s Cave, they must reckon with a different view of the world than they had before. This new knowledge of how the world really works does not fit within the existing frames and forms of society, and they must now walk in the world knowing what most do not, and wishing they never learned it themselves. The whistleblower will avoid people and places that trigger traumatic memories and feelings of humiliation, paranoia, or despair. This is likely to include self-withdrawal from social contacts and abandoning hobbies. Most whistleblowers will also report an increase in physical pain and fatigue. Whistleblowers often (78%) suffer from declining physical health post-disclosure.[32]

Instead of resembling the sort of rebellious, inspirational hero they are often depicted as, many whistleblowers suffer an existence comparable to Saint Sebastian (martyr) or Job (biblical figure). The media continue to personify the act of whistleblowing in the whistleblower (ignoring the institutional response), and the public often only engages with the grotesque truth of retaliation if presented in beautiful aesthetic like a magazine profile (imagine Francisco Goya’s “Saturn Devouring His Son” on display at the Prado Museum in Madrid). No one wants to accept that an embodied and vulnerable person is made to suffer so severely in a sacrificial battle for the common good.[33]

“Whistleblower”

Rather than abstract figures, whistleblowers are embodied, relational beings and, like everyone, their minds and bodies are vulnerable to demise. The experience of whistleblower retaliation is chaotic. The identity crisis that results from the aftermath of blowing the whistle can lead to an un-doing of the person. Previously held and stable views of self are thrown into disarray, leading to an unraveling of one’s identity and an experience of derealization.[34]

Retaliation robs whistleblowers of their identities as capable and successful professionals. Having spoken up, they are no longer seen as valid subjects deserving of basic respect, and so become targets of various kinds of retaliation and ridicule. Having spoken up, they are no longer seen as sufficiently valid to hire and, instead, they are excluded from recruitment processes. Finally, they are denied subjectivity in social interactions. They are seen as the “other” and shunned by former friends.[35]

A boundary appears to emerge and these subjects find themselves on the outside.

This experience plunges whistleblowers into an existential crisis. The human mind works hard to avoid these crises, and may clutch the stigmatized, controversial identity of “whistleblower” as a psychic lifeline, seeing no other option for a normative identity and preferring it over “leaker” or “activist” or worse. The experience will often leave whistleblowers’ minds stuck in static time and their lives paralyzed by the trauma. Those who are able to survive severe retaliation intact, often live the remainder of their lives in a state the Japanese refer to as “the freedom of one who lives as already dead.” [36]

“First one is enveloped by death, then one becomes the death by which one was enveloped and so goes on to live in a new way.” [37]

Power and the Dance of Dissent

Power is complex and circulating between the person being retaliated against and the organization which is retaliating. Some call this the “Dance of Dissent.”

The nature and extent of retaliation can be viewed as a balance of power between whistleblower and wrongdoer. Retaliation will likely be worse when the institution senses a threat to its resources due to the disclosure: if their exposed conduct involves harm to the public, if the legitimacy of the organization is threatened, or if the wrongdoing has already become systemic to the organization. If the organization is heavily dependent upon the wrongdoing for resources, the more a whistleblower attempts to disrupt the wrongdoing, the more the corporation will resist and retaliate. If the whistleblower is a senior employee, the company is more likely to make an example of the “defector.” In these situations, the retaliation may even rise to intentional “punishment.”[38]

Individuals who are connected to the illicit actions in some ways are likely to view whistleblowers as threats to the system they are still a part of. For managers and co-workers who directly engaged in the exposed wrongdoing, or have been tacit observers to it, their immediate and natural response is to deny or minimize the illicit behavior. Anyone who stands to benefit from the unethical activity is a candidate for administering punishment.[39]

Implicated individuals may be fearful of losing status, reputation and material rewards. Faced with feelings of apprehension and helplessness caused by the thought of losing resources, individuals may see retaliation against the whistleblower as a way to prevent that from happening. Rather than risk losing the benefits they may reap from the unethical behavior, individuals are likely to try to discredit the whistleblower and the allegations, in an effort to keep the established system from unraveling. As the system continues, the potential threat of whistleblowers to this “house of cards” becomes more dangerous and

Defense of a collective identity may also trigger a negative response to a whistleblower’s actions. Group members who share strong collective identities may feel overly protective of one another and, thus, choose to retaliate against whistleblowers they view as trying to disrupt these strong ties. Blowing the whistle on something like systemic corruption can represent a perceived threat to one’s group or system. These threats, in turn, activate cognitive and emotional processes. A norm of self-interest is likely to encourage the actor to do what is necessary to maintain the status quo.[41]

A Precarious Ledge

Whistleblowers are dependent on institutions and infrastructures (and their relational interdependence), for their material survival after speaking up against wrongdoing. The whistleblower is under relentless pressure in precarious living conditions. After losing their livelihood, profession, and income—whistleblowers may eventually be forced to give up their fight to avoid homelessness and/or bankruptcy. Many whistleblowers will eventually lose their homes and their families, and around half will file for bankruptcy. “A typical fate is for a nuclear engineer to end up selling computers at Radio Shack.”[42]

After making disclosures, a whistleblower’s income plummets while expenses rack up with relocation to a new home, legal costs, medical costs after losing insurance, costs for re-training in a new field, and credit fees and interest during the period of post-disclosure unemployment. The average shortfall during this period is $32,580 a year, and for those who are fired or otherwise lose earnings, the average shortfall is $76,291 a year. Even when whistleblowers are allowed to return to work, they can expect their average earnings to drop 67% post-disclosure.[43]

The time and work spent on disclosures and surviving the aftermath is entirely unpaid, unless there is an eventual lawsuit decision with compensatory damages, but that often takes years. However, the required activities of a whistleblower post-disclosure are a “full-time, all-consuming job in and of itself.” Virtually all (97%) whistleblowers report spending more than 100 hours on disclosure-related activities and 39% report spending more than 1,000 hours. Only the whistleblower has the knowledge and experience to provide lengthy and detailed descriptions of the wrongdoing and any subsequent retaliation. Such work is often carried out alone, unsupported and uncompensated.[44]

Because whistleblowers are usually met with character assassination and smear campaigns, in addition to managing the disclosures, whistleblowers are also forced into a self-advocacy role as a necessary defense in this time of precarity. If the whistleblower’s name is made public, a self-advocacy role is not optional and is essential to effective whistleblowing and personal survival. Time is spent seeking help from journalists, politicians, regulators, and lawyers—all of whom require different presentations of case information.[45]

If the whistleblower decides to also seek justice for the post-disclosure aftermath, it becomes a second campaign requiring as much cost and effort as the original claim. In both cases, time is required to prepare for and engage in lengthy court cases: compiling evidence, researching legal rights, studying organizational policies, assisting investigations, and advocating for political support.[46]

This time spent on disclosures might otherwise be devoted to seeking further employment, retraining, and engaging in the self-care required to mitigate the adverse health effects of whistleblowing-related stress. Instead, that required work is postponed. Concurrently, whistleblowers often deny the vulnerability they experience. Many suffer severe financial loss, but prefer to hide it due to social stigma around wealth and status. Similarly, whistleblowers also find themselves coerced to subvert outward signals of their internal suffering and terror, “in the name of effective lobbying.”[47]

Pointless Is the Point

Whistleblowers are an antithesis to cultures of secrecy, which are fertile for corruption due to the lack of disinfecting sunlight. As of 2022, 52% of organizations surveyed with revenue exceeding $10 billion said they experienced fraud in the past two years, the highest level in 20 years of research; 18% of those companies reported more than $50 million in financial impact due to the fraud incident. One-quarter (24%) of the fraud reported was asset misappropriation (illegal activities in the workplace). The perpetrator of the most severe fraud was identified to be internal 31% of the time and collusion between internal/external actors 26% of the time.[48]

Whistleblowers are desperately needed, yet U.S. whistleblower protection laws (an inconsistent web of employment law protections claiming to encourage disclosures of evidence of wrongdoing by offering “protections” from retaliation) dependably fail to actually protect employees. Existing schemes are not working for the majority they are supposed to serve and are based on flawed assumptions about the tangible and material experiences of speaking out. Some critics have gone so far to allege the current whistleblower laws are a “cynical attempt to entrap whistleblowers in a procedural abyss” and to fool employees into revealing their identity in order to make them easier targets for attack.[49]

Indeed, it is a cruel lie to call these laws “protections” when the best they offer is a small chance for an insufficient “remedy” after the fact—and even that still requires years of additional abuse and subjugation to obtain. Further, once an employee goes to a regulator in the U.S., there is a significant chance the employee will face additional retaliation by the regulator on behalf of the corporation or in support of business interests generally.[50]

This societal structure of whistleblowing puts the burden on individuals to alleviate systemic informational problems. Yet at the same time, whistleblower laws focus on what is done to whistleblowers (retaliation) and frequently neglect investigation into the original issues the employee raised. When policies compel employees to put themselves at risk and fulfill their presumed ethical obligations to come forward and disclose wrongdoing, it raises a question if that compulsion is ethical due to the personal devastation that will likely follow.[51]

Because a successful whistleblower brings down corrupt people in high places simply by exposing information, it is foolish to not recognize the incredible risk inherent in threatening the status and livelihood of those in powerful positions, and the incentive they have to bury that information and anyone who knows about it. The bare minimum the U.S. must do today is formally criminalize retaliation against whistleblowers. The laws and precedent for such legislation already exist in prosecutions of people for obstruction of justice and for witness-tampering but are rarely used outside of murder cases.[52]

A whistleblower who turns to regulators is ultimately a witness and informant; thus, there is no reason the same laws that protect someone directly assisting the Department of Justice on a criminal investigation should not apply to a whistleblower disclosing misconduct under other federal statutes. There also needs to be an independent mechanism for this process outside of the captured labor agencies. As of now, the ability (if any) for labor agencies to refer cases to the U.S. DOJ is unclear. Further, the process for seeking assistance directly from the U.S. DOJ is even more unclear and whistleblowers are likely to face similar issues of capture, at least for intake, as the captured labor agencies.[53]

Until there is at least some deterrent for employers to retaliate against whistleblowers (i.e., jail time instead of a relatively small fine), we should expect the devastating experience that is destined in certain types of whistleblowing to continue. This deters would-be whistleblowers from coming forward, instead of deterring institutions from engaging in misconduct.

Hazlina Shaik Md Noor Alam, “Whistleblowing When It Hurts: Whistleblower Gaslighting and Institutional Secrecy,” International Conference on Law, Environment and Society, October 2019; Multinational Monitor, “Blowing the Whistle on Corporate Wrongdoing: An Interview with Tom Devine,” Vol. 23, No. 10, October/November 2002. ↑

Brian Martin and Will Rifkin, “The Dynamics of Employee Dissent: Whistleblowers and Organizational Jiu-Jitsu,” Public Organization Review, 4: 221–238 (2004); Hannah Bloch-Wehba, “The Promise and Perils of Tech Whistleblowing,” Northwestern University Law Review, March 7, 2023; Brita Bjorkelo and Ole Jacob Madsen, “Whistleblowing and Neoliberalism: Political Resistance in Late Capitalist Economy,” Psychology & Society, Vol. 5, No. 2, (2013); Richard Alexander, “The Role of Whistleblowers in the Fight against Economic Crime,” Journal of Financial Crime, Vol. 12, No. 2, (2004). ↑

Adam R. Nicholls, et al., “Snitches Get Stitches and End Up in Ditches: A Systematic Review of the Factors Associated with Whistleblowing Intentions.” Frontiers in Psychology, October 5, 2021; Matthew McClearn, “A Snitch in Time,” Canadian Business, Vol. 77 Issue 1, 60-70 (Dec 2003); Kate Kenny, Marianna Fotaki,, and Wim Vandekerckhove, “Whistleblower Subjectivities: Organization and Passionate Attachment,” Organization Studies (2018). ↑

Michael Davis, “Some Paradoxes of Whistleblowing,” Business & Professional Ethics Journal, Vol 15, No 1 (1996). ↑

Brian Martin, “Illusions of Whistleblower Protection,” UTS Law Review, No. 5 (2003); Kate Kenny, “Censored: Whistleblowers and Impossible Speech,” Human Relations, Vol. 71, No. 8 (2018). ↑

Kenny et al., “Whistleblower Subjectivities”; Kaeten Mistry and Hannah Gurman, eds., Whistleblowing Nation: The History of National Security Disclosures and the Cult of State Secrecy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020); Martin and Rifkin, “The Dynamics of Employee Dissent.” ↑

Herman T. Tavani and Frances Grodzinsky, “Trust, Betrayal, and Whistle-Blowing: Reflections on the Edward Snowden Case,” ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society, 44(3), Special Issue on Whistle-Blowing (2014); Davis, “Some Paradoxes of Whistleblowing.” ↑

Tavani and Grodzinsky, “Trust, Betrayal, and Whistle-Blowing.” ↑

Carmen R. Apaza and Yongjin Chang, “What Makes Whistleblowing Effective: Whistleblowing in Peru and South Korea,” Public Integrity, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Spring 2011); Martin and Rifkin, “The Dynamics of Employee Dissent”; Kenny et al., “Whistleblower Subjectivities”; Davis, “Some Paradoxes of Whistleblowing.” ↑

Kenny et al., “Whistleblower Subjectivities”; Jawad Khan, et al., “Examining Whistleblowing Intention: The Influence of Rationalization on Wrongdoing and Threat of Retaliation,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health; 19(3): 1752 (February 2022); Davis, “Some Paradoxes of Whistleblowing”; Khan, et al., “Examining Whistleblowing Intention”; Nicholls et al., “Snitches Get Stitches and End Up in Ditches.” ↑

April White, “Truth Be Told,” Harvard Business School (December 6, 2021), https://www.alumni.hbs.edu/stories/Pages/story-bulletin.aspx?num=8524; Nicholls et al., “Snitches Get Stitches and End Up in Ditches”; Martin, “Illusions of Whistleblower Protection”; Khan, et al., “Examining Whistleblowing Intention.” ↑

Apaza et al., “What Makes Whistleblowing Effective.” ↑

Jacqueline Garrick and Martina Buck, “Whistleblower Retaliation Checklist: A New Instrument for Identifying Retaliatory Tactics and Their Psychosocial Impacts After an Employee Discloses Workplace Wrongdoing,” Crisis, Stress, and Human Resilience (CSHR): An International Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2 (September 2020); McClearn, “A Snitch in Time.” ↑

Garrick and Buck, “Whistleblower Retaliation Checklist”; Shaik, “Whistleblowing When It Hurts.” ↑

Apaza et al., “What Makes Whistleblowing Effective.” ↑

Kathy Ahern, “Institutional Betrayal and Gaslighting: Why Whistle-Blowers Are So Traumatized,” The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, Vol. 32, No. 1, 59–65 (2018); Apaza et al., “What Makes Whistleblowing Effective”; Khan et al., “Examining Whistleblowing Intention”; Kate Kenny, Marianna Fotaki, and Stacey Scriver, “Mental Health as a Weapon: Whistleblower Retaliation and Normative Violence,” Journal of Business Ethics, 160, 801–815 (2019). ↑

Peter G. van der Velden, et al., “Mental Health Problems Among Whistleblowers: A Comparative Study,” Psychological Reports, 122 (2): 632-644 (April 2019); Garrick and Buck, “Whistleblower Retaliation Checklist”; Ahern, “Institutional Betrayal and Gaslighting”; Peter G. van der Velden, et al., “Mental Health Problems Among Whistleblowers.” ↑

Martin, “Illusions of Whistleblower Protection”; Garrick and Buck, “Whistleblower Retaliation Checklist”; Martin and Rifkin, “The Dynamics of Employee Dissent”; Kenny, et al., “Mental Health as a Weapon”; Mark Worth, “Diagnosing Retaliation: The Traumatizing and Insidious Effects of Whistleblowing,” Whistleblower Network News, https://whistleblowersblog.org/features/diagnosing-retaliation-the-traumatizing-and-insidious-effects-of-whistleblowing/ ↑

United States Department of Justice, “Guilty verdict on all counts for illegal alien who murdered whistleblower in an illegal labor conspiracy” (November 1, 2022), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdga/pr/guilty-verdict-all-counts-illegal-alien-who-murdered-whistleblower-illegal-labor; US DOJ, Three Men Indicted In Conspiracy to Kill Whistleblower, (December 13, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdga/pr/three-men-indicted-conspiracy-kill-whistleblower ↑

Ben Farmer and Peta Thornycroft, “Mystery of murdered whistleblower who uncovered hospital corruption,” The Telegraph, October 11, 2022, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/terror-and-security/mystery-murdered-whistleblower-babita-deokaran-who-uncovered/; News24, “Silenced: Why Babita Deokaran was murdered,” https://specialprojects.news24.com/silenced/index.html ↑

Aaron Keller, “‘I Hope and Pray that You Die Alone and Scared’: Family Members of Victim Slam ‘Piece of Sh*t’ Restaurant Boss for Brutal Murder of Employee,” Law & Crime, November 30, 2021, https://lawandcrime.com/crime/i-hope-and-pray-that-you-die-alone-and-scared-family-members-of-victim-slam-piece-of-sht-restaurant-boss-for-brutal-murder-of-employee/ ; Stephen Williams, “Kakavelos found guilty of first-degree murder, nine other charges,” The Daily Gazette, June 17, 2021, https://dailygazette.com/2021/06/17/kakavelos-found-guilty-of-first-degree-murder-nine-other-charges/ ↑

Jeremy Kuzmarov, “There’s Something Rotten in Denmark:” Frank Olson and the Macabre Fate of a CIA Whistleblower in the Early Cold War,” Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 3 (2020). ↑

“Karen Silkwood dies in mysterious one-car crash, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/karen-silkwood-dies-in-mysterious-one-car-crash; Howard Kohn, “Karen Silkwood: The Case of the Activist’s Death,” Rolling Stone, January 13, 1977, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/karen-silkwood-the-case-of-the-activists-death-52287/; Jennifer Latson, “The Nuclear-Safety Activist Whose Mysterious Death Inspired a Movie,” Time, November 13, 2014; David Burnham, “US Says Lost Plutonium,” The New York Times, (Jan 3 1975), https://www.nytimes.com/1975/01/03/archives/us-says-lost-plutonium-is-only-a-small-amount.html. ↑

Chris Oregan, “The Mysterious Death of an Enron Exec,” CBS (April 10, 2002), https://web.archive.org/web/20090315083648/https://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2002/04/10/eveningnews/main505845.shtmlPatrick Martin, “The strange and convenient death of J. Clifford Baxter—Enron executive found shot to death,” World Socialist Web Site, (January 28, 2002), https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2002/01/enro-j28.html; Brian Ross, “Enron Destroyed Documents by the Truckload,” ABC News, (January 29, 2002), https://abcnews.go.com/WNT/story?id=130518&page=1 ↑

Paul F. Lipold, “’Striking Deaths’ at their Roots: Assaying the Social Determinants of Extreme Labor-Management Violence in US Labor History—1877–1947,” Social Science History, 38(3-4), 541-575 (2014); Jonah Walters, “Labor Day is May 1,” Jacobin, September 7, 2015, https://jacobin.com/2015/09/labor-day-may-first-american-labor-movement-haymarket/; “The Labor Movement,” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/labor-movement; PBS, “Labor Wars in the U.S.,” PBS: The Mine Wars, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/theminewars-labor-wars-us/; Richard Alexander, “The Role of Whistleblowers in the Fight Against Economic Crime,” Journal of Financial Crime, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 131-138 (2004). ↑

Kenny, “Censored: Whistleblowers and Impossible Speech”; Garrick and Buck, “Whistleblower Retaliation Checklist.” ↑

Garrick and Buck, “Whistleblower Retaliation Checklist.” ↑

Garrick and Buck, “Whistleblower Retaliation Checklist”; Ahern, “Institutional Betrayal and Gaslighting.” ↑

Martin and Rifkin, “The Dynamics of Employee Dissent.” ↑

Shaik, “Whistleblowing When It Hurts”; Martin and Rifkin, “The Dynamics of Employee Dissent”; Neil Weinberg, “He Investigated Dubious Firings for U.S. Then He Was Fired,” Bloomberg, July 21, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-07-21/he-investigated-suspicious-firings-for-u-s-then-he-was-fired ↑

Mistry, “Whistleblowing Nation” ↑

C. Fred Alford, Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002); Peter G. van der Velden, et al., “Mental Health Problems Among Whistleblowers”; Craig J. Bryan, et al., “Measuring Moral Injury: Psychometric Properties of the Moral Injury Events Scale in Two Military Samples,” Assessment, 1-14, (2015); Garrick and Buck, “Whistleblower Retaliation Checklist”; Alec M. Smidt and Jennifer J. Freyd, “Government-mandated Institutional Betrayal,” Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 19:5, 491-499 (2018); Kenny, et al., “Mental Health as a Weapon.” ↑

Alford, Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power; Britannica, “St. Sebastian,” Encyclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Sebastian ↑

Kenny, “Censored: Whistleblowers and Impossible Speech”; Kenny, et al., “Mental Health as a Weapon”; Kate Kenny and Marianna Fotaki, “The Costs and Labour of Whistleblowing: Bodily Vulnerability and Post-disclosure Survival,” Journal of Business Ethics, 182, pp. 341-64 (2023). ↑

Kenny, “Censored.” ↑

Alford, Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power; Kenny, et al, “Whistleblower Subjectivities.” ↑

Alford, Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. ↑

John J. Sumanth, David M. Mayer, and Virginia S. Kay, “Why Good Guys Finish Last: The Role of Justification Motives, Cognition, and Emotion in Predicting Retaliation Against Whistleblowers,” Organizational Psychology Review, Vol. 1, Issue 2, (2011); Kenny, et al., “Mental Health as a Weapon”; Martin and Rifkin, “The Dynamics of Employee Dissent”; Alford, Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. ↑

Sumanth, et al., “Why Good Guys Finish Last.” ↑

Id. ↑

Id. ↑

Alford, Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power; Kenny, et al., “Mental Health as a Weapon”; Kenny and Fotaki, “The Costs and Labour of Whistleblowing. ↑

Kenny and Fotaki, “The Costs and Labour of Whistleblowing. ↑

A full-time job is generally 1,700 hours per year. Kenny and Fotaki, “The Costs and Labour of Whistleblowing.” ↑

Kenny and Fotaki, “The Costs and Labour of Whistleblowing.” ↑

Kenny and Fotaki, “The Costs and Labour of Whistleblowing.” ↑

Alford, Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power; Kenny and Fotaki, “The Costs and Labour of Whistleblowing.” ↑

Sharfa Hassan, et al., “Unethical Leadership: Review, Synthesis and Directions for Future Research,” Journal of Business Ethics, 183. 1-40 (2022); PwC, “PwC’s Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey” (2022). https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/forensics/economic-crime-survey.html; Dr. Devakumar Jacob, “Collateral Damage: An Urgent Need for Legal Apparatus for Protection of the Whistleblowers & RTI Activists,” IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 4, Ver. VII (April 2014). ↑

Martin, “Illusions of Whistleblower Protection”; Kenny and Fotaki, “The Costs and Labour of Whistleblowing.” ↑

Martin, “Illusions of Whistleblower Protection”; Vicky Nguyen, Liz Wagner and Felipe Escamilla, “OSHA Whistleblower Investigator Blows Whistle on Own Agency,” NBC Bay Area, February 24, 2015, https://www.nbcbayarea.com/news/local/osha-whistleblower-investigator-blows-whistle-on-own-agency/77171/ ↑

Kenny and Fotaki, “The Costs and Labour of Whistleblowing”; Martin, “Illusions of Whistleblower Protection”; Bloch-Wehba, “The Promise and Perils of Tech Whistleblowing.” ↑

Sibel Edmonds and William Weaver, “To Tell the Truth,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 62, No. 1 (Jan/Feb 2006); Anthony R. Petruzzi, Adrienne B. Kirshner, “Beware of Potential Criminal Implications for the Improper Handling of a Whistleblower Investigation,” Inside Counsel (October 21, 2015); Martin, “Illusions of Whistleblower Protection”; United States v. Stoker, 706 F.3d 643, 646 (5th Cir. 2013). ↑

18 U.S. Code § 1512 – Tampering with a witness, victim, or an informant; 18 U.S. Code § 1513 – Retaliating against a witness, victim, or an informant; Thomas Brewster, “FBI’s San Francisco Chief: We Heart Apple, They Train Our Cops,” Forbes (January 16, 2018), https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2018/01/16/apple-and-the-fbi-are-closer-than-you-think ↑

Although I had already read a lot of the source materials you used, you did a fantastic job summarizing key points/findings. All government retaliation investigators should be required to read your article as well as Dr. Jennifer Freyd's DARVO website https://pages.uoregon.edu/dynamic/jjf/defineDARVO.html, C. Fred Alford's Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power, and Whistleblowers of America Founder Jackie Garrick's book The Psychosocial Impacts of Whistleblower Retaliation. Thank you for all your work on this topic. Good luck with your legal case.